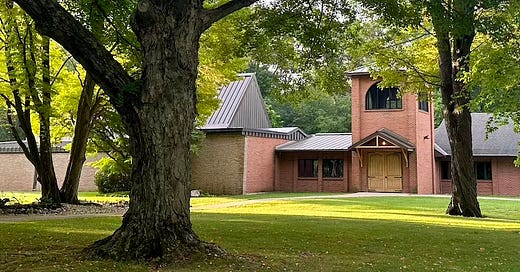

St. Gregory’s Abbey is an Episcopal monastery for men in the sandy woods of southwest Michigan. I spend four days there in September, exhausted after a six-week bout with Covid.

It is a spare and simple place. You put the sheets on your own bed. The bathroom is down the hall. Lunch and dinner are served the traditional Benedictine way, in silence with someone reading aloud from a book. A serve-yourself breakfast is available only until 7:30 a.m. In the fridge, there is just skim milk and soy milk.

It is spare, but it is enough.

It feels like an ancient place. The chapel smells like wood and old books. The liturgy is spoken and sung very slowly and quietly. I like to sit and listen rather than try to get the tones right or muddy the sound of monks who’ve been chanting multiple times a day together for decades. The Daily Office is six or seven times a day, starting at 4:00 a.m. I made it to 6:00 a.m. prayers one morning, but otherwise slept in most days. Worship was haunting and beautiful, if sometimes also like a liturgical museum.

It is also a quirky, progressive place. Go to afternoon tea to chat with the monks and you might find yourself in conversation about Portlandia or Star Trek, Brutalist architecture, or the inanity of recent Supreme Court rulings. Meals while I was there included pork vindaloo, scrambled eggs with potatoes and a waffle, and Philly cheesesteaks. The book being read at meals was Burning Rainbow Farm: How a Stoner Utopia Went Up in Smoke, about two tragic, ludicrous deaths that happened in 2001 just a few miles from the abbey. Their library has volumes in Latin but also an encyclopedia of science fiction. There are portraits of former abbots and of the African monk, Benedict the Black.

In addition to human things, there is a lake with beavers and frogs, walking trails used mostly by deer, and while I was there, two sand cranes who walked back and forth across the campus like they owned it, squawking like dinosaurs.

I hadn’t been to St. Gregory’s in over a decade. When I said that to the guestmaster, his eyes got wide and he said, “A lot has changed since then.” I wasn’t sure what he meant - to my eyes, things hadn’t changed much. I did notice one of the monks had become the full-time cook. That a gravel parking lot had been left to grow into a grassy patch. That two monks now walk with a cane, including when they celebrate the Eucharist.

One night, a fellow guest was walking across the courtyard with me after dinner and asked:

“How long can this place last? There are so few monks and they’re getting old!”

I imagine everyone who comes to St. Gregory’s asks this question, out loud or to themselves. I certainly had. I imagine the monks ask it, too. A few decades ago, there were a couple dozen monks at St. Gregory’s. Now there are six.

Even though many churchy people I know have thought about becoming a monk or nun, including me, most of us don’t go through with it. And most folks who “try on” the vocation as visitors or novices eventually choose to leave. As I once heard a monk say: “They comes and they goes, but mostly they goes.”

There are about fifteen Episcopal monasteries across the country, depending how you count, for both men and women. One monastery is home to just two sisters. Another is home to almost twenty brothers. The rest fall in between, with most communities at three, four, or five. I was surprised how even the smallest seem (from their websites) to have large numbers of lay associates active and involved.

But I imagine many of them also ask, “How long can this place last?”

Many churches also ask themselves this question.

The decline of religion, Christianity, and the mainline church is a steady hum in the background of my life. Even when I was a kid in the 1980s, I knew my family was in a minority in our university neighborhood because we went to church on Sundays.

Still, there are times when the hum bursts into a clap.

Like the time I went to sign up for a library card at the mainline seminary in Indianapolis and found myself walking into what I thought would be the library — but turned out to be a big empty room.

And the time Adam and I were driving cross-country and spent a night in Rochester, New York. The next morning, I wanted to drive by the divinity school there – Colgate Rochester Crozer. We made our way up a steep, tree-lined driveway and arrived in the parking lot, but — the school was gone. The new signs were for the American Cancer Society and “Divinity Estate,” a wedding venue.

To my surprise, I burst into tears. I can think of many good reasons why the school sold its campus and moved downtown. But in that moment, the sight of beautiful but mostly empty buildings, where a vibrant spiritual learning center used to be, and of the abandoned student apartments, where a community of spiritually curious seminarians used to be… felt less like innovative change and more like loss.

Steady loss has become a part of American church culture. The pandemic heightened this. There are fewer people, fewer kids, fewer clergy. Less money, less staff, less seminarians. And this has all become ordinary. An institution and way of being church that many of us love — because through it, God has loved us — is disappearing. It won’t disappear entirely, but it will have a much smaller, much different, footprint than it once did.

And I wonder if we all have a case of compounded grief. I know I do.

Compounded grief may be why so many church folks responded on social media with such passion and at such length to a farewell letter posted by a burned out pastor who resigned his position outside Chicago this summer – whether critiquing or defending him. Grief makes us angry and afraid, but those emotions often bubble quietly beneath the surface because we’re coping, just trying to live and work. Until something pricks a hole in you and then it all comes rushing out.

For me, and maybe for you, too, the mainline church has been a haven in a cynical world. A goofy, disorganized place of welcome, good folks, shared meals, music, and a sense of mystery about who God is. Maybe it’s flakey that mainline Christians aren’t more bossy about Who or What God is, how everyone should live, or what everyone should believe. Maybe this doesn’t sell a lot of widgets or attract people the way evangelicalism, Cross Fit, or Taylor Swift do.

Not organized religion so much as disorganized religion. (A term I first encountered in a book by Kathleen Norris.)

Admittedly, I have also experienced mainline church culture as a little boring, a little trying-too-hard, a little sloppy. Churches often feel anxious and mostly focused on committees, effectiveness, worship as a checklist, vestments, supporting the right causes. Certainly, I have experienced or seen sexism, racism, classism, homophobia, and apathy in mainline churches, as well.

My own mainline love also took a tumble after I became a parish priest, when my church life became more about running a business than being part of a community, more about anxiety and administration than welcome or mystery. There’s more to the story, but I left parish ministry in 2017.

Still, I have seen mainline churches bring people together in safe, gentle, spiritual spaces. Mainline people have worked and succeeded at normalizing women’s ordination, gay and lesbian ordination, same sex marriage, antiracism, welcoming refugees, welcoming people with autism, welcoming transgender and non-binary folks, and more, in their churches. Things that don’t make the news, things many people don’t realize churches are capable of. But these things have either come too late or failed to address the deeper malaise that people seem to feel for church, Christianity, and institutional religion.

A monk at St. Gregory’s once told a friend of mine, “Many people tell us their ideas to improve the monastery. But none of them are interested in becoming monks.”

When I was a young parish priest, I was full of ideas – I believed we could make church relevant, entrepreneurial, exciting – that we could “save” the church. But I no longer experience much of Jesus or the gospel in thinking in this way.

Andrew Root writes that our response to the decline of church and Christian life should not be to stop and “wait for God,” as he says. In other words: gather, pray, and grow relationships with one another — in other words, the things I most loved about church as a kid: being together, sharing meals, serving neighbors in need, sitting with wonder and mystery, feeling part of a community. Then see what the Holy Spirit seems to arouse or invite within and around us.

Should a monastery or a church hang it all up because numbers are small or aging? Abandon their community, their ministry, their vows? (Baptismal vows, if not monastic ones.) What’s really important? What is faith and ministry about, after all?

Gah, I’ve tried to say too much here already, probably because of my own grief - my own lack of answers, my own anger and fear about the future of this church that I have loved, and has loved me back.

I didn’t share any of this with the other guest that night on the path after dinner. I chickened out. I shrugged my shoulders and said, “Maybe it’s up to the Holy Spirit.”

She sighed and said, “Well, I suppose that’s true.”

It is enough.

MOVE

Some news: Adam and I moved from Indianapolis to Des Moines, Iowa, in the first week of October. Here, we are closer to Adam’s family, including to three little nephews under the age of four. We both work remotely, so this doesn't involve a job change. Indianapolis was a wonderful place for us - three years with beloved old friends, adventures in a new city, and rich experiences of church and faith. We were sad to leave but we are excited for this next place on our journey, out on the prairie.

WHAT I’VE BEEN READING

What You Sow Is a Bare Seed: A Countercultural Christian Community during Five Decades of Change, (2023) by Celeste Kennel-Shank. I have always loved the idea that a church could be more like an intentional community or monastery and The Church of Christ in Washington, D.C., was just like that. My friend Celeste grew up there. She did the research and many interviews to compile a fascinating history.

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, (2009) by Annette Gordon-Reed. An African American historian writes the story of the complications, cringey-ness, and yet clear affection of the family of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: their ancestors, their extended family, their children, their descendants. It’s in-depth so slow going, but fascinating.

When Church Stops Working, (2023) by Andrew Root and Blair Bertrand. The book I mention, above. A shorter summary of his longer, denser books and a radical approach to congregational decline: mostly “waiting for God,” which does not come naturally to Americans.

MY LATEST BOOK and my ADVENT BOOK

Everyday Connections: Reflections and Practices for Year B Sermon prep! Personal journaling! Small group bonanza! I love this book because it can do it all. The reflection questions are meaty and head-scratchy, not useless and boring. Fill out the form on my website to get a free, signed bookplate mailed to you, for this or any of my books.

Advent in Narnia. This is a book I wrote for adults and big kids, to go deeper into Advent and connect faith with imagination, back in 2015. Still going strong. Hope you love it as much as I do.

New here? Want to know more? For more about me, my spiritual direction practice, and my other books and writings, check out my website.

Blessings,

Heidi

What heartfelt and true words. Sadly similar to my own experience in ministry. And those in power simply don’t want to face the truth.

Oh Heidi. Thank you for putting all this grief into words. I feel it with you and don't know how to describe what I'm feeling exactly... except that it is there and it is real. I really loved this essay and hope you had a blessed retreat.