The amazing and frightening thing about human beings is how adaptable we are. We say, “How could someone live through that?” And yet, people do. Most of the men who were kidnapped and imprisoned in El Salvador are still living, as of this writing. Somehow, the two million people who are still alive in Gaza still wake up every morning. This week, I read an article in The New Yorker about a family of nine in Sudan, trying to get from war-ravaged Khartoum to their family village in the mountains. Extortion, rape, torture, and murder are everywhere.

My daily life is paradise in comparison. And yet, I stumble around, wondering how to keep functioning, as we seem to have entered a proxy civil war. It is not a “hot” war, with bombs and bullets, or even a cold war, but there are acts of terrorism, institutional destruction, looting, refugees, and casualties. There is cultural upheaval, abandonment of civil norms, the mocking and dehumanizing of enemies. The future is a blank: uncertain and unstable. What our nation used to consider baseline values and norms, including our Constitution, are being ignored, dismantled, and twisted.

I find myself thinking of my maternal grandparents, Murray and Ingrid, who lived through the Nazi occupation of Norway. They were in Oslo in April 1940, when the Nazis invaded. My grandmother was an obstetric nurse. My grandfather was in the merchant marine. His appendix had ruptured that week and he was sequestered in the sick bay, so he missed the land battles and U-boat attacks that took the lives of many of his peers — or drove them to run for Sweden (which remained neutral in World War II, causing Norwegians to despise them for decades after).

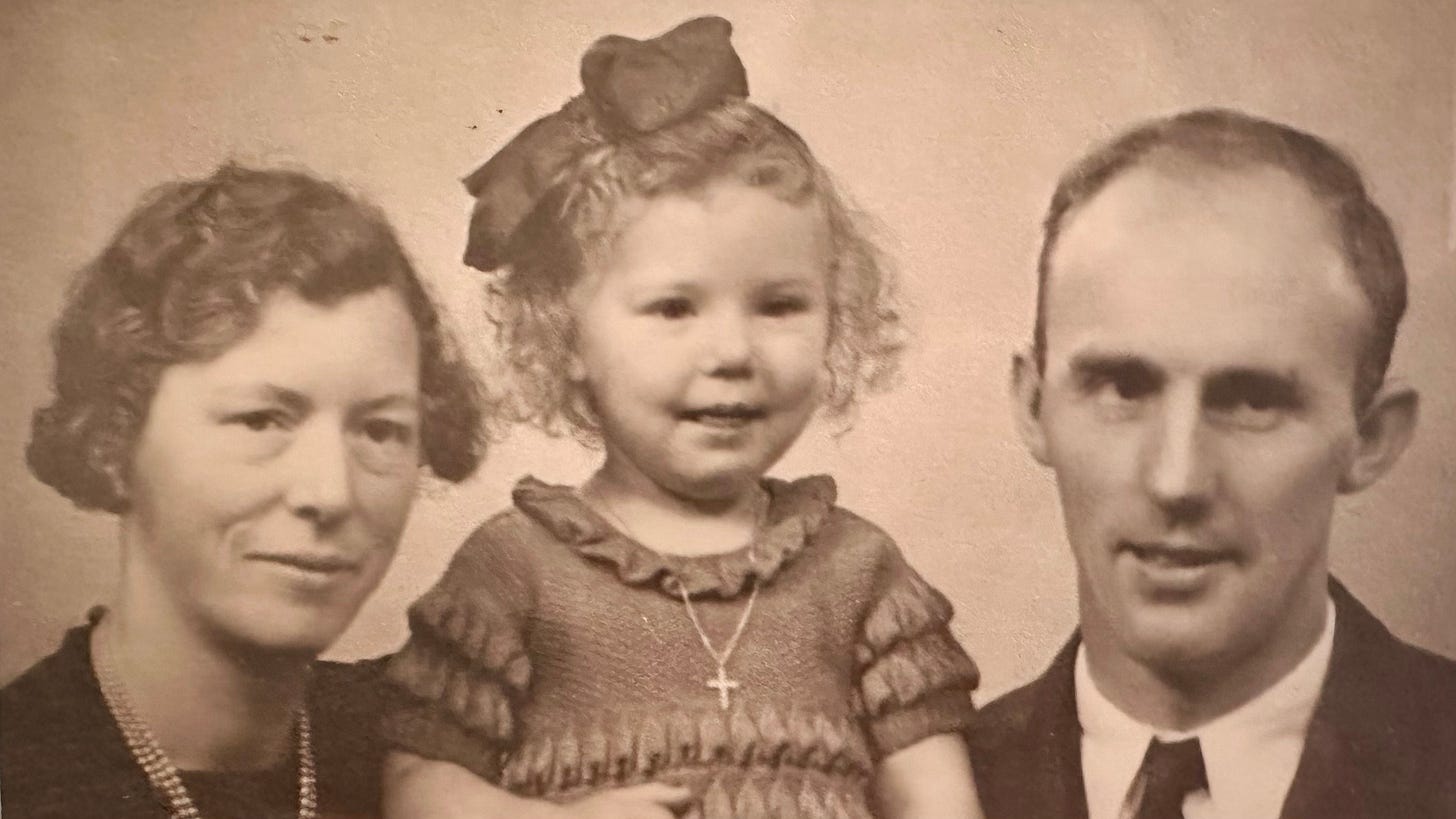

The Norwegian occupation was a walk in the park compared to other places in Europe at that time, but life in those years still was traumatic and precarious. Murray and Ingrid married - they were over thirty, quite old for the time - and left the big city to move to his hometown, Horten. Just because it was a small town did not mean it was safe: Horten is on the shores of the Oslofjord, the highway for boats and ships, so a significant battalion of soldiers was posted there. Murray’s parents, shopkeepers, were kicked out of their house so that Nazi officers and their families could move in. This is where my grandparents went to wait out the war and start a family.

When I was a kid, reading about Europe in the 1930s as the Nazis were taking over, especially stories about Jewish children and families, I remember thinking to myself, “I would have gotten out of there right away!” Everything seems simple when you’re a kid. But now, as a middle-aged adult, leaving my country seems unthinkable. My life is woven and rooted here: friends, family, my elder father, work, church, the landscape of my beloved Chicago and Midwest. They are me and I am them.

Many people become refugees, but many others do not leave home, even in the face of a war, a pandemic, a crackdown, a coup, or an occupation. They stay put. Sometimes, that means people die. But more often, for better or worse, the people who stay endure, survive, and play a part in the way their country changes through a horrible crisis into the next thing.

My grandparents didn’t emigrate to America until 1949; they stayed in Horten.

And so, I wonder what they would say if I could ask them: How did you do it? How did you live, day to day?

They died in the 1990s, so I can’t. And I wonder if they would just shake their heads at me, even if I could ask, not interested in reflecting on that time — preferring to forget. I do have the stories my mother liked to tell us over and over (she died in 2016), about her parents in wartime, which is also when she was born.

My mother told us that, since news was censored by the Nazis and radios were contraband, her father hid one under the floorboards of the family hytte, or summer cottage (in Norway, usually not far from the year-round house). He would sneak out there at night, take out the radio and tune into the BBC, trying to find out what was happening in the war. He did not speak English but the BBC was broadcasting in Norwegian and many other European languages during that time, trying to break through Nazi censorship.

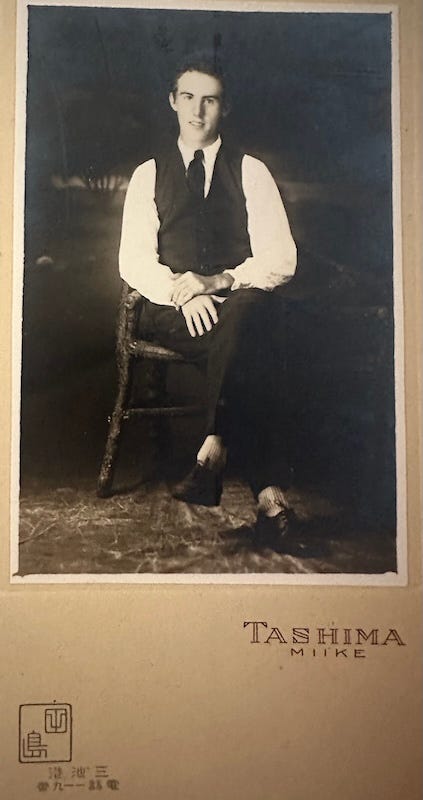

My grandfather had spent his young adulthood traveling the world as a navigator onboard large ships. He had a portrait photo taken of himself in Japan (below), where he also bought a set of hand-painted china for his mother, which we still have.

During the war, he was marooned in his family’s small town, but he traveled as he could: on his bicycle, past the soldiers posted at the crossroads, to collect information for his family and friends about was happening beyond their shores. Probably, also, he did it for himself.

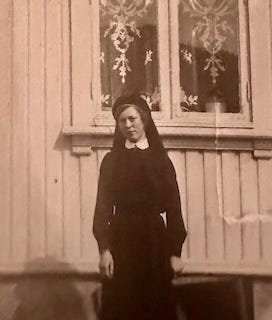

My grandmother grew up above the Arctic Circle, in a family of poor dirt farmers. As a young woman in the 1930s, she escaped her complicated family and the bleakness of the North to train as a nurse in Oslo.

She survived the war by focusing on her little daughter, it seems to me. A story my mom loved to tell us was that, before her second birthday, my grandparents rode their bicycles deep into the countryside to smuggle ingredients to make her a cake. They crafted special belts with pockets to hold eggs without breaking them, hidden under their coats, and they saved empty medicine bottles for the farmer to fill with milk. The soldiers used to eat chocolate bars, slathered with butter, in front of townspeople, who didn’t have such things and might go hungry. But my grandmother figured out a way to make her toddler a birthday cake.

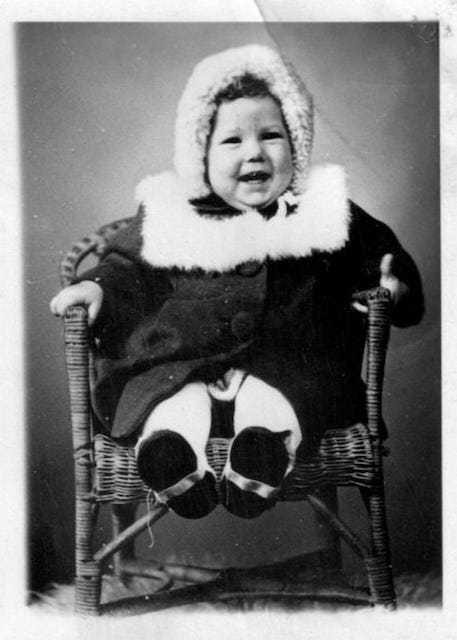

Like my seafaring grandfather, she had a sense of adventure. Unlike him, she had a love of showering people with kindness, hugs, and presents. My mother must have been a delightful distraction. (Here she is, below, probably around Christmas in 1943.)

These are the stories my grandparents chose to tell their kids about the war. But I often wonder if there were other things - horrific things - they also knew, saw, or heard about, but did not want to remember. There was an execution camp, for Russian prisoners of war, on an island close to Horten. There was a prison camp twelve miles away. I learned that their infamous Norwegian Nazi collaborator, Vidkun Quisling, the puppet head of Norway’s government during the occupation, gave a speech in their town in 1942, threatening to send people who had celebrated Constitution Day to prison. After the war, collaborators like him were imprisoned in those same camps, and often executed, as Quisling was just before my mother’s third birthday.

Years after the war, my grandparents decided to immigrate to America. They raised my mom and my uncle, who was born a few months later, in Jersey City, New Jersey, which is where my grandfather, unable to speak much English, was able to find a job as a church custodian. My grandmother was able to continue to work as a nurse. They lived quiet lives: went to work, wrote letters to family, shopped for Norwegian foods and sundries in the Norwegian enclave of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, watched television, and spent a lot of time on their own, just the two of them. They went back to Norway to see family regularly. My grandfather longed to move back (his English was never very good), but my grandmother refused to put an ocean between her and her grandchildren.

My grandparents weren’t heroes. They weren’t part of any active resistance; they didn’t put their lives on the line to try to overthrow the occupation. I’m no hero, either. I haven’t even shown up for a protest yet. I’m an introvert with an often painfully sensitive body and brain; crowds, even moderate ones, make me feel sick these days. Maybe you are an introvert or a part-time hermit, too. Or home with young kids. Or facing illness. Or busy with a job you can’t take much time off from. Or otherwise not very good at being a fighter, an activist, a challenger, or a prophet. (I am very grateful for those folks, because I can’t be one of them and we need them.)

Solitude and resistance are not opposed to one another.1 Introverts are not inherently people of apathy and avoidance. My grandparents kept mostly to themselves, but helped hold up the world in the place where they lived. If nothing else, they carried the goodness of humanity forward despite being surrounded by great evil and destruction.

From their lives, I hear an answer to my question: “How do I survive this?” — find something you care about and tend it: a hidden radio, a child, a place, a group, making art, fixing things, caring for someone who needs it. Through tending something, you can give yourself and your community hope.

Help hold up the world in the place where you live.

Help carry the goodness of humanity forward.

My grandparents died in the United States, but told their children they wanted their ashes to be returned to their home country, to Horten. Norway is a country of rocky mountains and cliffs and graveyard space is at a premium, so they were buried in my great-grandparents’ grave. No marker shows their names. But we know they are there.

Heidi

MY BOOKS

Everyday Connections: Reflections and Practices for Year C (also Year A and Year B)- a devotional for individuals, clergy and lay, and small groups: with meaty questions, humor, ideas and juxtapositions. Scripture can be life changing… even for progressive Christians!

Holy Solitude - solitude as spiritual practice, including a week of devotions about solitude as a form of resistance.

Advent in Narnia - reflections for adults about Advent through the lens of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, by C.S. Lewis. With a small group study guide and suggestions for hosting an Advent gathering at a church for kids.

Free bookplates. I will mail you two signed bookplates when you fill out a form on my website. No strings attached and I don’t keep your address.

THINGS I’M READING

Persuasion, by Jane Austen. I tried watching the new PBS series, “Miss Austen,” and decided I wanted to reread a novel instead, which makes me miss my mother, who adored Austen. I also found I had to rewatch the 1995 movie, “Persuasion,” with Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds.

Magdalene and What the Living Do, by Marie Howe. Howe just won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. She is a marvel. Two of my favorites are “Annunciation” and “Magdalene - The Seven Devils” (“The first was that I was very busy”).

Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, by Robert C. O’Brien. I like to reread childhood books. It is nice to visit people and places I once knew well, but haven’t seen in a while. This one is about a mouse and a bunch of rats. It’s great.

Escape from Khartoum, by Nicholas Niarchos, in The New Yorker. This is the article I referred to, above; “A family of nine’s desperate attempt to find safety in Sudan.” (For now, not behind a paywall.)

The Sun (magazine). A magazine of stories in the form of letters to the editor, photos, interviews, quotes, fiction, and “Readers Write”: a collection of very short pieces, written in the first person, on a particular theme. Ad-free. It was founded in 1974 and feels like it was put together by a bunch of people you know - of many ages, races, levels of education, parts of the country, some incarcerated, etc. Subscribe and you won’t regret it.

New here? Want to know more? For more about me and my other books and writings, check out my website.

Thanks for reading.

I wrote a week of devotions in Holy Solitude about this, pp. 75-92.

Thanks for this Heidi. I enjoyed learning about your grandparents- what an amazing story about the cake. And I really appreciate your thoughts about introverts and resistance. I also cannot tolerate crowds and now with two preschoolers, at least one with special needs, I have little capacity for public protest but am doing my best to tend to my bit of the world. Thanks for sharing g and helping us introverts feel seen and encouraged in our part.

This was such a sacred take on all the realities! THANK YOU friend!